Rodney Hall is a rare being, an author with over 30 novels published, two Miles Franklin awards, three Booker prize nominations, countless other awards and an Order of Australia medal. And amid these plaudits Rodney has never compromised his vision for excellence in literature.

Text: by Ian Dixon; Photos: Ross Bird, 2007

With that in mind, you can imagine my trepidation when Rodney asked me to co-write his 1991 award-winning classic novel Captivity Captive into a screenplay.

It was clear that to do this classic Australian period novel justice we would have to embrace that art of collaboration and compromise.

There was potential for this dramatic project to blow up in our faces. With Film Victoria funding us the stakes were high and the team, including producer, script editor and Rodney and I, all have a range of character traits.

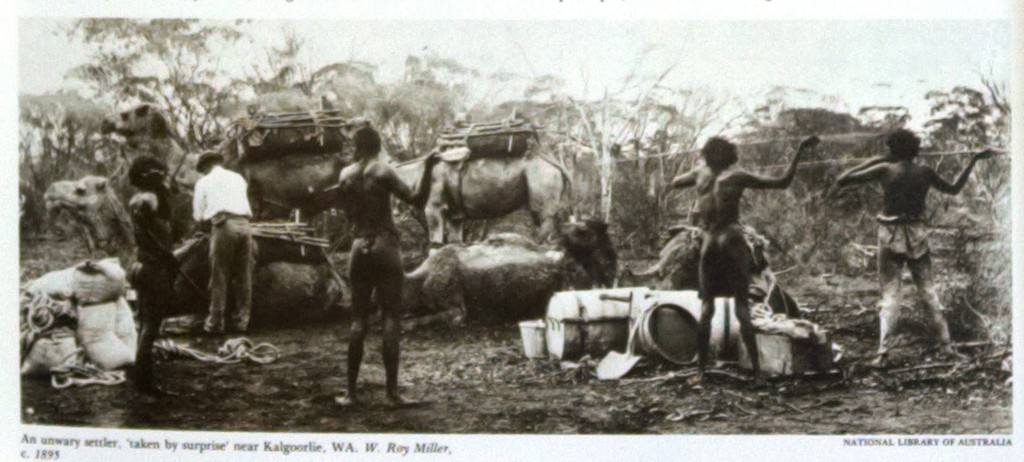

Captivity Captive centres on a border crossing of the human soul. This is a story of an unsolved murder mystery: three siblings from a Catholic family found murdered in a paddock in New South Wales in 1898 – with no clues to go on. The story’s theme centres on sexuality and love misconstrued and misinterpreted. When I think of those early days of collaboration, I remember how deferential I was to Rodney’s position as an author.

He had studied with legendary novelist Robert Graves and been mentored by poet John Manifold. I considered the lessons in poetic representation Rodney taught me to be totally applicable to film. But then there was the producer, Chris Warner – intelligent and deeply respecting of the novel – who required the timely delivery of a workable modern screenplay. Also I had to consider script editor, David Rapsey, whose job was to focus our poetic interpretation into a functional story form.

Love – the pinnacle value of our film – was of vital interest to Rodney. Sexual obsession in the form of love sat uncomfortably at the feet of our illustrious script editor. I soon understood that if I were to be a writer of calibre, I would need to learn from their experience whilst simultan-eously remaining strong about my position. My resistance had a purpose, namely I had to stay focused on the goal at hand, which was to deliver a world-class screenplay that warranted a solid mid-range production budget.

Love – the pinnacle value of our film – was of vital interest to Rodney. Sexual obsession in the form of love sat uncomfortably at the feet of our illustrious script editor. I soon understood that if I were to be a writer of calibre, I would need to learn from their experience whilst simultan-eously remaining strong about my position. My resistance had a purpose, namely I had to stay focused on the goal at hand, which was to deliver a world-class screenplay that warranted a solid mid-range production budget.

Let’s take a step back and look at the ingredients. We had funding to write a screenplay with an acknowledged genius of literature. I had read Captivity Captive and loved the novel immensely. At this stage, Rodney had seen my VCA graduating short film Cut (1998) and decided (after rejecting offers as high as Hollywood) that I should be the director of this film. Gulp! He deeply valued his book, in which he spoke from his soul. He was more than an expert in his field. He was a wordsmith of the highest international standard. How was I to convince him that, in a screenplay, words are merely a vehicle for the visual material of the shot film?

In the beginning, we worked closely on the imagery of the film. Rodney taught me to absorb myself in the material such that the images arose effortlessly. He considered true art to arise from an indescribable place in the collective unconscious. Although I was a declared Freudian and questioned such Jungian notions, I had to admit that ‘surrendering’ to the energy of the piece, rather than ‘grabbing the bull by the horns’ and steering it had resulted in significant poetic beauty. The process was directly opposite to my painstaking training in structural analysis for cinema. However, as Rodney pointed out, the ‘blueprint’ for any story was embedded within the idea itself, not in some imposed structure. I took note. We worked through draft after draft involving such exercises as blindfolding the designated writer (usually me) and asking them to place themselves imaginatively within a given set piece from the novel. As improvising writers, we invented our way out of the darkness.

In the beginning, we worked closely on the imagery of the film. Rodney taught me to absorb myself in the material such that the images arose effortlessly. He considered true art to arise from an indescribable place in the collective unconscious. Although I was a declared Freudian and questioned such Jungian notions, I had to admit that ‘surrendering’ to the energy of the piece, rather than ‘grabbing the bull by the horns’ and steering it had resulted in significant poetic beauty. The process was directly opposite to my painstaking training in structural analysis for cinema. However, as Rodney pointed out, the ‘blueprint’ for any story was embedded within the idea itself, not in some imposed structure. I took note. We worked through draft after draft involving such exercises as blindfolding the designated writer (usually me) and asking them to place themselves imaginatively within a given set piece from the novel. As improvising writers, we invented our way out of the darkness.

This applied as much to structure as it did to scenarios and imagery. Scenes were arranged on an intuitive level, rather than an intellectual one. This invention on Rodney’s part managed to shake my tightly held opinions of cinematic structure, of cause and effect chains, allowing for greater creative freedom in the image. The resultant screenplay was beautiful, but unwieldy. Classic filmic moments tore themselves away from cliché to suggest a film both raw and vital. The filmic story, however, did not manifest in succinct form. Whereas the writer of literature had the liberty of letting the story dictate itself, the temporal art of film prevented such meanderings (except perhaps under the genius of Carl Th. Dreyer or John Cassavetes).

The next phase was to hand this draft over to our eager producer, Chris Warner. Chris had been attracted to the work since he approached Rodney to adapt this novel into a feature film a decade earlier. Both a producer and screenwriter, Chris was now keen to rewrite the film himself – in consultation with Rodney and myself (though I was in no illusion as to whose opinion he most required). The genre he chose was the ‘courtroom mystery’. Chris served the characters and story well, but some-how the essence of the screenplay had become too much of genre, not enough of artistry. Chris felt somewhat defeated, not by the script, but by the controlling forbearance of his two bratty counterparts. Rodney and I were at this stage working very much as a team (albeit an antagonistic team to anyone working around us). Enter David Rapsey – the Film Victoria appointed script editor with a polished sense of story and defined approach to story form. It was from David that I learned the importance of obeying the story engine and ‘value’ of a narrative its own terms. Under David’s guidance – the script focused on the incestual interplay of the adult offspring of this Catholic family in pioneer Australia and the tragedy of their dogma-imposed repression – a repression leading to murder.

Rodney’s love of this story was paramount and I had grown to love the story equally. David pared the narrative back to its constituent elements and the story of ‘taboo love’ came to the fore.

Rodney’s love of this story was paramount and I had grown to love the story equally. David pared the narrative back to its constituent elements and the story of ‘taboo love’ came to the fore.

The only problem was that David did not seem to share the same conception of human relations that Rodney and I did. David was a trained gestalt psychologist and business advisor. He was immune to the kind of dysfunctional love that seemed to come so naturally to Rodney and I. As mentioned, I was an unashamed Freudian and Rodney eschewed all preconceived psychological templates. We literally drove each other mad. Rodney changed both story and form like the perennial improviser he was. David insisted that the tracks were laid and we should remain on target whilst trying to establish if Rodney and I were telling the same story. Meanwhile, I was trying to lock the story into an expansive directorial vision. Our funding for the script edit was fast running past David’s patient capacity to help us and I was trying to balance the influences of both these advisors. We were all frustrated and pulling in three different directions.

I could see Rodney’s point in wanting a deeply intelligent and inventive filmic work that would challenge Australian film. During this phase, Australian film was in the doldrums creatively, artistically and in terms of international sales (certainly nothing we viewed was exciting us much). This is where our script was sealed up in a sleepy tomb. Film Victoria will one day see their investment come to fruition, but the way forward now is to attach a named director who shares our vision. We have a template for the story, which we believe is largely workable. The structural work is done, the balance of expectation and reality is strong, and the sense of tragic foreboding and deep love still remains.

However the screenplay still needs work and I managed to convince Rodney to let me write the next draft alone. He agreed, with just one proviso: that the motivation for all three murders remain the same – love. How the world will receive this challenging film remains to be seen. What matters now is that the collaborators have a common understanding. The film promises to be both a classic Australian myth and modern masterpiece. We’ll keep you posted on its progress.

Sexual obsession in the form of love sat uncomfortably at the feet of our illustrious script editor.

Captivity Captive centres on a border crossing of the human soul. This is a story of an unsolved murder mystery about three siblings from a Catholic family found murdered in a paddock in New South Wales in 1898 – without any clues to assist.