In the 60s and 70s, American independent filmmaker John Cassavetes challenged film art in ways still significant today.

Text: by Ian Dixon; Photos: Krystal Seigerman

His maverick vision for screen performance was groundbreaking. This article will visit some of Cassavetes’ innovations then illuminate them by reference to my own feature film Crushed (2009).

Cassavetes instilled performance excellence in such films as Shadows (1960) and A Woman under the Influence (1974). Although a figure from our past, his singular focus on performance authenticity still serves as an excellent model for the modern filmmaker. Cassavetes’ unique films incorporated improvisational and kinaesthetic aspects (the ability ‘to move with sensation’) to a degree rarely matched, even today (Dowd, 2006).

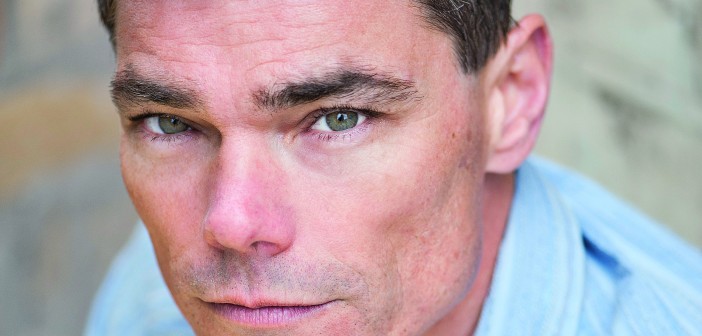

Ian Dixon is a

professional screen-

writer, director and actor working in the Australian film and

television industry.

He has been funded by Film Victoria and Screen Australia and worked on most Melbourne-based

Television programs.

The iconoclastic Cassavetes ignored classical form, focus and line-crossing rules. Instead, he drew upon Cinéma Vérité conventions to show the flawed beauty of the human face. In Cassavetes films, a dramatic beat might be the reverse emphasis of its predecessor. This technique of ‘Flipping’ helped him exploit the element of surprise in his films (Carney, 2001, p. 160). Although reported to have improvised during shooting this is strictly not true. He always reworked and fine-tuned his material before shooting (Martin, 2005). Nevertheless, his filmmaking relied heavily on improvisation and experiment.

Cassavetes’ approach to acting developed through early influences at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts, consisting largely of Stanislavskian training. Cassavetes therefore insisted that performing mechanically rendered the actor a ‘wound-up machine’ (Stanislavsky, 1980, p. 71). He therefore developed a lifelong commitment to authenticity, listening and responding.

The major elements of Cassavetes’ acting were dedication to realism, authenticity and avoidance of ‘indicative’ performance traits (Carney, 2001). Acting of such raw honesty was disturbingly real even by modern standards. Yet, despite his star status as an actor (including The Dirty Dozen (1967) and Rosemary’s Baby (1968)), Cassavetes directed his major works with no financial help from Hollywood industry. He grew acutely aware of the ways an unthinking director could ‘unconsciously intimidate the performer’ (Carney, 2001, p. 157).

Thus, Cassavetes’ work as an actor directly influenced his filmmaking. He used the camera, not just a box for recording images, but as a kinaesthetic device. This included his own physical gyrations whilst operating camera – effectively imitating the actor’s point of view (Carney, 1994). Sometimes he would hand the camera to other actors. Cassavetes’ camera communicated via his own kinaesthetic presence and physical relationship to the actors, thus creating a spatial metaphor for the emotional distance between characters. For Cassavetes, these sensibilities were more important than the practical concerns of filming.

Based on this, I implemented Cassavetes’ approach within my own film Crushed. Perhaps the most satisfying scene to shoot was scene 71 where the heroine, Nathalia (Georgina Capper), consoled her traumatised student, Audrey (Miranda Nation). For this scene, the Cassavetean element of surprise contributed to the on-screen authenticity. In the shooting of Crushed, no actor knew that Audrey’s motivation was based on her love for Nathalia (except Miranda). Actors were therefore surprised to discover this unseen motivating factor.

Scene 71 was thematically flipped from the previous scene where all characters interacted on the level of outer conflict. Now Audrey faced Nathalia on an inner level. Having established this contrast, I emulated Cassavetes’ use of unforeseen possibilities. In Cassavetes’ sense, my characters could now guide the rhythm of the drama ‘off the scene’ rather than formulaically (Carney, 2001, p. 152). I therefore warned actors and crew to be prepared for anything just as Cassavetes had (Carney, 2001). Thus, Miranda was instructed to follow her impulses and continue regardless of Georgina’s response.

Like Cassavetes, we had to accommodate for lighting and boom shadow. I also prepared cinematographer David Hawkins for the possibility of erratic movement. After weeks of observing David and Georgina’s growing kinaesthetic relationship, I decided not to operate camera myself. David was technically proficient and obviously dexterous enough to shoot the improvisation. Just as Cassavetes made camera operators out of actors, I made an actor out of my camera operator.

The experiment proved successful. As the improvisation unfolded, Georgina responded admirably and maintained physical frontality for the camera (Bordwell, 1986), whilst David kept both actors in frame. Naturally, the difficulty for continuity department was to maintain verisimilitude for the reverse angle. For this over-shoulder reverse shot, Georgina did not need to reciprocate her startled performance authenticity. She merely needed to repeat her improvised lines and body positions to facilitate shooting Miranda’s angle. Most of this improvisation was retained in the final cut resulting in the tense, kinaesthetic engagement for the cinema audience. The interplay of narrative, active character and camera work presented a unique experience for actors and audience alike.

Although I never attempted to imitate Cassavetes, the application of his radical methodology rendered Crushed a unique modern film. I therefore discovered the timeless value of strong, immediate performances – as was Cassavetes’ vital contribution to film art. Both camera and actors became elements of the style and meaning of the film. For this I am indebted to Cassavetes and urge young filmmakers to study his works and discover how interactive camera and authenticity can instill originality in their films – both in performance and style.

Reference List

Bordwell, D., & Thompson,

K. (1986). Film art: An introduction (2nd ed).

New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Carney, R. (1994). The films of John Cassavetes:

Pragmatism, modernism and the movies.

United States of America: Cambridge University Press.

Carney, R. (Ed.). (2001). Cassavetes on Cassavetes.

New York: Faber & Faber Inc.

Dowd, I. (2006). Ideokinesis:

The 9 lines of movement. Kinetics 1.

Melbourne: Victorian College of the Arts,

University of Melbourne.

Martin, A. (2005). Low-budget cinema:

beware the cliché. Retrieved

April 22, 2007, from

http://www.afc.gov.au/newsandevents/afcnews/feature/adrian_martin/newspage_220.aspx

Stanislavsky, C. (1980).

An actor prepares (E. R. Hapgood, Trans.).

London: Eyre Methuen Ltd. (Original work published 1937)